Paul Newman, one of the last of the great 20th-century movie stars, died Friday at his home in Westport, Conn. He was 83.

The cause was cancer, said Jeff Sanderson of Chasen & Company, Mr. Newman’s publicist.

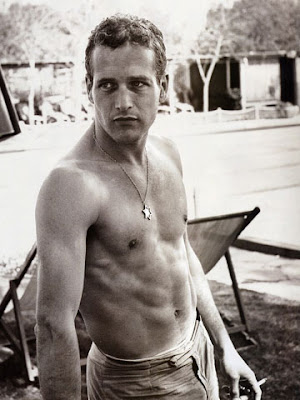

If Marlon Brando and James Dean defined the defiant American male as a sullen rebel, Paul Newman recreated him as a likable renegade, a strikingly handsome figure of animal high spirits and blue-eyed candor whose magnetism was almost impossible to resist, whether the character was Hud, Cool Hand Luke or Butch Cassidy.

He acted in more than 65 movies over more than 50 years, drawing on a physical grace, unassuming intelligence and good humor that made it all seem effortless.

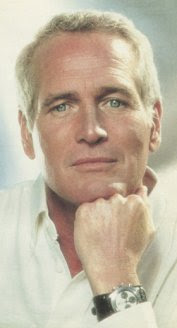

Yet he was also an ambitious, intellectual actor and a passionate student of his craft, and he achieved what most of his peers find impossible: remaining a major star into a craggy, charismatic old age even as he redefined himself as more than Hollywood star. He raced cars, opened summer camps for ailing children and became a nonprofit entrepreneur with a line of foods that put his picture on supermarket shelves around the world.

Mr. Newman made his Hollywood debut in the 1954 costume film “The Silver Chalice,” but real stardom arrived a year and a half later, when he inherited from James Dean the role of the boxer Rocky Graziano in “Somebody Up There Likes Me.” Mr. Dean had been killed in car crash before the screenplay was completed.

It was a rapid rise for Mr. Newman, but being taken seriously as an actor took longer. He was almost undone by his star power, his classic good looks and, most of all, his brilliant blue eyes. “I picture my epitaph,” he once said. “Here lies Paul Newman, who died a failure because his eyes turned brown.”

Mr. Newman’s filmography was a cavalcade of flawed heroes and winning antiheroes stretching over decades. In 1958 he was a drifting confidence man determined to marry a Southern belle in an adaptation of “The Long, Hot Summer.” In 1982, in “The Verdict,” he was a washed-up alcoholic lawyer who finds a chance to redeem himself in a medical malpractice case.

And in 2002, at 77, having lost none of his charm, he was affably deadly as Tom Hanks’s gangster boss in “Road to Perdition.” It was his last onscreen role in a major theatrical release. (He supplied the voice of the veteran race car Doc in the Pixar animated film “Cars” in 2006.)

Few major American stars have chosen to play so many imperfect men.

As Hud Bannon in “Hud” (1963) Mr. Newman was a heel on the Texas range who wanted the good life and was willing to sell diseased cattle to get it. The character was intended to make the audience feel “loathing and disgust,” Mr. Newman told a reporter. Instead, he said, “we created a folk hero.”

As the self-destructive convict in “Cool Hand Luke” (1967) Mr. Newman was too rebellious to be broken by a brutal prison system. As Butch Cassidy in “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid” (1969) he was the most amiable and antic of bank robbers, memorably paired with Robert Redford. And in “The Hustler” (1961) he was the small-time pool shark Fast Eddie, a role he recreated 25 years later, now as a well-heeled middle-aged liquor salesman, in “The Color of Money” (1986).

That performance, alongside Tom Cruise, brought Mr. Newman his sole Academy Award, for best actor, after he had been nominated for that prize six times. In all he received eight Oscar nominations for best actor and one for best supporting actor, in “Road to Perdition.” “Rachel, Rachel,” which he directed, was nominated for best picture.

“When a role is right for him, he’s peerless,” the film critic Pauline Kael wrote in 1977. “Newman is most comfortable in a role when it isn’t scaled heroically; even when he plays a bastard, he’s not a big bastard — only a callow, selfish one, like Hud. He can play what he’s not — a dumb lout. But you don’t believe it when he plays someone perverse or vicious, and the older he gets and the better you know him, the less you believe it. His likableness is infectious; nobody should ever be asked not to like Paul Newman.”

But the movies and the occasional stage role were never enough for him. He became a successful racecar driver, even competing at Daytona in 1995 as a 70th birthday present to himself. When he won his event, he made the Guinness Book of Records as the oldest winner in his race class.

In 1982, as a lark, he decided to sell a salad dressing he had created and bottled for friends at Christmas. Thus was born the Newman’s Own brand, an enterprise he started with his friend A. E. Hotchner, the writer. More than 25 years later the brand has expanded to include, among other foods, lemonade, popcorn, spaghetti sauce, pretzels, organic Fig Newmans and wine. (His daughter Nell Newman runs the company’s organic arm.) All its profits, of more than $200 million, have been donated to charity, the company says.

Much of the money was used to create a string of Hole in the Wall Gang Camps, named for the outlaw gang in “Butch Cassidy.” The camps provide free summer recreation for children with cancer and other serious illnesses. Mr. Newman was actively involved in the project, even choosing cowboy hats as gear so that children who had lost their hair because of chemotherapy could disguise their baldness.

Several years before the establishment of Newman’s Own, on Nov. 28, 1978, Scott Newman, the oldest of Mr. Newman’s six children and his only son, died at 28 of an overdose of alcohol and pills. His father’s monument to him was the Scott Newman Center, created to publicize the dangers of drugs and alcohol. It is headed by Susan Newman, the oldest of his five daughters.

Mr. Newman’s three younger daughters are the children of his 50-year second marriage, to the actress Joanne Woodward. Mr. Newman and Ms. Woodward both were cast — she as an understudy — in the Broadway play “Picnic” in 1953. Starting with “The Long, Hot Summer” in 1958, they co-starred in 10 movies, including “From the Terrace” (1960), based on a John O’Hara novel about a driven executive and his unfaithful wife; “Harry & Son” (1984), which Mr. Newman also directed, produced and helped write; and “Mr. & Mrs. Bridge” (1990), James Ivory’s version of a pair of Evan S. Connell novels, in which Mr. Newman and Ms. Woodward played a conservative Midwestern couple coping with life’s changes.

When good roles for Ms. Woodward dwindled, Mr. Newman produced and directed “Rachel, Rachel” for her in 1968. Nominated for the best-picture Oscar, the film, a delicate story of a spinster schoolteacher tentatively hoping for love, brought Ms. Woodward her second of four best-actress Oscar nominations. (She won the award on her first nomination, for the 1957 film “The Three Faces of Eve,” and was nominated again for her roles in “Mr. & Mrs. Bridge” and the 1973 movie “Summer Wishes, Winter Dreams.”)

Mr. Newman also directed his wife in “The Effect of Gamma Rays on Man-in-the-Moon Marigolds” (1972), “The Glass Menagerie” (1987) and the television movie “The Shadow Box” (1980). As a director his most ambitious film was “Sometimes a Great Notion” (1971), based on the Ken Kesey novel.

In an industry in which long marriages might be defined as those that last beyond the first year and the first infidelity, Mr. Newman and Ms. Woodward’s was striking for its endurance. But they admitted that it was often turbulent. She loved opera and ballet. He liked playing practical jokes and racing cars. But as Mr. Newman told Playboy magazine, in an often-repeated quotation about marital fidelity, “I have steak at home; why go out for hamburger?”

Beginnings in Cleveland

Paul Leonard Newman was born on Jan. 26, 1925, in Cleveland. His mother, the former Teresa Fetzer, was a Roman Catholic who turned to Christian Science. His father, Arthur, who was Jewish, owned a thriving sporting goods store that enabled the family to settle in affluent Shaker Heights, Ohio, where Paul and his older brother, Arthur, grew up.

Teresa Newman, an avid theatergoer, steered her son toward acting as a child. In high school, besides playing football, he acted in school plays, graduating in 1943. After less than a year at Ohio University at Athens, he joined the Navy Air Corps to be a pilot. When a test showed he was colorblind, he was made an aircraft radio operator.

After the war Mr. Newman entered Kenyon College in Ohio on an athletic scholarship. He played football and acted in a dozen plays before graduating in 1949.

Arthur Newman, a strict and distant man, thought acting an impractical occupation, but, perhaps persuaded by his wife, he agreed to support his son for a year while Paul acted in small theater companies.

In May 1950 his father died, and Mr. Newman returned to Cleveland to run the sporting goods store. He brought with him a wife, Jacqueline Witte, an actress he had met in summer stock. But after 18 months Paul asked his brother to take over the business while he, his wife and their year-old son, Scott, headed for Yale University, where Mr. Newman intended to concentrate on directing.

He left Yale in the summer of 1952, perhaps because the money had run out and his wife was pregnant again. But almost immediately, the director Josh Logan and the playwright William Inge gave him a small role in “Picnic,” a play that was to run 14 months on Broadway. Soon he was playing the second male lead and understudying Ralph Meeker as the sexy drifter who roils the women in a Kansas town.

Mr. Newman and Ms. Woodward were attracted to each other in rehearsals of “Picnic.” But he was a married man, and Ms. Woodward has insisted that they spent the next several years running away from each other.

In the early 1950s roles in live television came easily to both of them. Mr. Newman starred in segments of “You Are There,” “Goodyear Television Playhouse” and other shows.

He was also accepted as a student at the Actors Studio in New York, where he took lessons alongside James Dean, Geraldine Page, Marlon Brando and, eventually, Ms. Woodward.

Then Hollywood knocked. In 1954 Warner Brothers offered Mr. Newman $1,000 a week to star in “The Silver Chalice” as the Greek slave who creates the silver cup used at the Last Supper. Mr. Newman, who rarely watched his own films, once gave out pots, wooden spoons and whistles to a roomful of guests and forced them to sit through “The Silver Chalice,” which he called the worst movie ever made.

His antidote for that early Hollywood experience was to hurry back to Broadway. In Joseph Hayes’s play “The Desperate Hours,” he starred as an escaped convict who holds a family hostage. The play was a hit, and during its run, Jacqueline Newman gave birth to their third child.

On his nights off Mr. Newman acted on live television. In one production he had the title role in “The Death of Billy the Kid,” a psychological study of the outlaw written by Gore Vidal and directed by Arthur Penn for “Philco Playhouse”; in another, an adaptation of Ernest Hemingway’s short story “The Battler,” he took over the lead role after James Dean, who had been scheduled to star, was killed on Sept. 30, 1955.

Mr. Penn, who directed “The Battler,” was later convinced that Mr. Newman’s performance in that drama, as a disfigured prizefighter, won him the lead role in “Somebody Up There Likes Me,” again replacing Dean. When Mr. Penn adapted the Billy the Kid teleplay for his first Hollywood film, “The Left Handed Gun,” in 1958, he again cast Mr. Newman in the lead.

Even so, Mr. Newman was saddled for years with an image of being a “pretty boy” lightweight.

“Paul suffered a little bit from being so handsome — people doubted just how well he could act,” Mr. Penn told the authors of the 1988 book “Paul and Joanne.”

By 1957 Mr. Newman and Ms. Woodward were discreetly living together in Hollywood; his wife had initially refused to give him a divorce. He later admitted that his drinking was out of control during this period.

With his divorce granted, Mr. Newman and Ms. Woodward were married on Jan. 29, 1958, and went on to rear their three daughters far from Hollywood, in a farmhouse on 15 acres in Westport, Conn.

That same year Mr. Newman played Brick, the reluctant husband of Maggie the Cat, in the film version of Tennessee Williams’s “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof,” earning his first Academy Award nomination, for best actor. In 1961, with “The Hustler,” he earned his second best-actor Oscar nomination. He had become more than a matinee idol.

Directed by Martin Ritt

Many of his meaty performances during the early ’60s came in movies directed by Martin Ritt, who had been a teaching assistant to Elia Kazan at the Actors Studio when Mr. Newman was a student. After directing “The Long, Hot Summer,” Mr. Ritt directed Mr. Newman in “Paris Blues” (1961), a story of expatriate musicians; “Hemingway’s Adventures of a Young Man” (1962); “Hud” (1963), which brought Mr. Newman a third Oscar nomination; “The Outrage” (1964), with Mr. Newman as the bandit in a western based on Akira Kurosawa’s “Rashomon”; and “Hombre” (1967), in which Mr. Newman played a white man, reared by Indians, struggling to live in a white world.

Among his other important films were Otto Preminger’s “Exodus” (1960), Alfred Hitchcock’s “Torn Curtain” (1966) and Jack Smight’s “Harper” (1966), in which he played Ross Macdonald’s private detective Lew Archer.

In 1968 — after he was cast as an ice-cold racecar driver in “Winning,” with Ms. Woodward playing his frustrated wife — Mr. Newman was sent to a racing school. In midlife racing became his obsession. A Web site — newman-haas.com — details his racing career, including his first race in 1972; his first professional victory, in 1982; and his partnership in a successful car racing team.

A politically active liberal Democrat, Mr. Newman was a Eugene McCarthy delegate to the 1968 Democratic convention and appointed by President Jimmy Carter to a United Nations General Assembly session on disarmament. He expressed pride at being on President Richard M. Nixon’s enemies list.

When Mr. Newman turned 50, he settled into a new career as a character actor, playing the title role — “with just the right blend of craftiness and stupidity,” Janet Maslin wrote in The New York Times — of Robert Altman’s “Buffalo Bill and the Indians” (1976); an unscrupulous hockey coach in George Roy Hill’s “Slap Shot” (1977); and the disintegrating lawyer in Sidney Lumet’s “Verdict.”

Most of Mr. Newman’s films were commercial hits, probably none more so than “The Sting” (1973), in which he teamed with Mr. Redford again to play a couple of con men, and “The Towering Inferno” (1974), in which he played an architect in an all-star cast that included Steve McQueen and Faye Dunaway.

After his fifth best-actor Oscar nomination, for his portrait of an innocent man discredited by the press in Sydney Pollack’s “Absence of Malice” (1981), and his sixth a year later, for “The Verdict,” the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in 1986 gave Mr. Newman the consolation prize of an honorary award. In a videotaped acceptance speech he said, “I am especially grateful that this did not come wrapped in a gift certificate to Forest Lawn.”

His best-actor Oscar, for “The Color of Money,” came the next year, and at the 1994 Oscars ceremony he received the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award. The year after that he earned his eighth nomination as best actor, for his curmudgeonly construction worker trying to come to terms with his failures in “Nobody’s Fool” (1994). In 2003 he was nominated as best supporting actor for his work in “Road to Perdition.” And in 2006 he took home both a Golden Globe and an Emmy for playing another rough-hewn old-timer, this one in the HBO mini-series “Empire Falls.”

Besides Ms. Woodward and his daughters Susan and Nell, , he is survived by three other daughters, Stephanie, Melissa and Clea; two grandchildren; and his brother.

Mr. Newman returned to Broadway for the last time in 2002, as the Stage Manager in a lucrative revival of Thornton Wilder’s “Our Town.” The performance was nominated for a Tony Award, though critics tended to find it modest. When the play was broadcast on PBS in 2003, he won an Emmy.

This year he had planned to direct “Of Mice and Men,” based on the John Steinbeck novel, in October at the Westport Country Playhouse in Connecticut. But in May he announced that he was stepping aside, citing his health.

Mr. Newman’s last screen credit was as the narrator of Bill Haney’s documentary “The Price of Sugar,” released this year. By then he had all but announced that he was through with acting.

“I’m not able to work anymore as an actor at the level I would want to,” Mr. Newman said last year on the ABC program “Good Morning America.” “You start to lose your memory, your confidence, your invention. So that’s pretty much a closed book for me.”

But he remained fulfilled by his charitable work, saying it was his greatest legacy, particularly in giving ailing children a camp at which to play.

“We are such spendthrifts with our lives,” Mr. Newman once told a reporter. “The trick of living is to slip on and off the planet with the least fuss you can muster. I’m not running for sainthood. I just happen to think that in life we need to be a little like the farmer, who puts back into the soil what he takes out.”