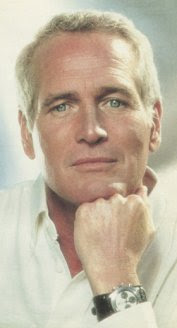

Actor Paul Newman dies at 83 The blue-eyed star of 'The Hustler,' 'Cool Hand Luke' and 'Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid' was at home. He had long battled cancer.

The blue-eyed star of 'The Hustler,' 'Cool Hand Luke' and 'Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid' was at home. He had long battled cancer.Paul Newman, the legendary movie star and irreverent cultural icon who created a model philanthropy fueled by profits from a salad dressing that became nearly as famous as he was, has died. He was 83.

Newman died Friday at his home near Westport, Conn., after a long battle with cancer, publicist Jeff Sanderson said.

Stunningly handsome, Newman maintained his superstar status while protecting himself from its corrupting influences through nearly 100 Broadway, television and movie roles. As an actor and director, he evolved into Hollywood's elder statesman, admired as much offscreen for his quiet generosity, unconventional business sense, race car daring, political activism and enduring marriage to actress Joanne Woodward.

Annoyed by the public's fascination with his resemblance to a Roman statue, particularly his Windex-blue eyes, Newman often chose offbeat character roles. In the 1950s and '60s, he helped define the American anti-hero and became identified with the charming misfits, cads and con men in film classics such as "The Hustler," "Hud," "Cool Hand Luke" and "Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid."

Newman's poker-game look in "The Sting" -- cunning, watchful, removed, amused, confident, alert -- summed up his power as a person and actor, said Stewart Stern, a screenwriter and longtime friend.

"You never see the whole deck, there's always some card somewhere he may or may not play," Stern said. "Maybe he doesn't even have it."

Newman claimed his success came less from natural talent than from hard work, luck and the tenacity of a terrier.

"Acting," he once said, "is really nothing but exploring certain facets of your own personality trying to become someone else." In early films, he said he tried to make himself fit the character but later aimed "to make the character come to me."

The actor was most proud, friends say, of his later, Oscar-nominated roles in "Absence of Malice," "The Verdict" and "Nobody's Fool," in which he dug deep into the complex emotions of ordinary men struggling for dignity, justice or a sense of connection. In 2003, he was nominated for an Oscar for his last feature film appearance, as a conflicted mob boss in "Road to Perdition." Two years later, at 80, he won an Emmy for playing a meddlesome father in "Empire Falls."

"He's a majestic figure in the world of acting," said director Arthur Penn, who worked with him in his early career. "He did everything and did it well."

Part of a generation of edgy, naturalistic New York actors who changed Hollywood in the '50s and '60s, Newman was often compared with fellow Method actors Marlon Brando and James Dean. Film critic David Ansen once observed that if the trim actor lacked the others' physical or psychic presence, he was more approachable, even when he played a heel.

"Newman," Ansen wrote, "is our great middleweight movie star."

Nominated eight times for Academy Awards in the best-actor category, Newman won only once, for "The Color of Money" (1986), in which he reprised the role of "Fast" Eddie Felson that he originated in 1961's "The Hustler." He also took home honorary Oscars in 1985 for career achievement and in 1993 for his humanitarian efforts. In later years, however, he boycotted awards shows despite continuing Oscar, Emmy and Tony nominations. He claimed he no longer owned a tuxedo.

In real life, Newman was "the quintessence of class, courtly without being old-fashioned," said Victor Navasky, former editor of the Nation, a liberal magazine in which Newman invested and wrote occasional columns. Private and complex, Newman was also a beer-loving, mischievous prankster and an idealist who took to the streets to protest the war in Vietnam.

He was thrilled, friends said, when he heard that he had made President Nixon's enemies list.

Married since 1958 to Woodward, his second wife, Newman cultivated a distinctly un-Hollywood lifestyle, shuttling between a homey New York apartment and a renovated farmhouse in woodsy Westport, Conn., from which he pursued passions including cooking and auto racing.

Highly competitive, Newman was drawn to the track, he told reporters, because in racing, unlike acting, the definition of "good" is not a murky matter of opinion. Although he began to race at 47, he was ranked among the sport's top 25% of drivers, his team placing second in the prestigious Le Mans endurance contest in 1979. At 70, he became the oldest driver to place in a professionally sanctioned auto race when his team took third in the 24-hour race at Daytona, Fla.

Still racing into his 80s, Newman escaped uninjured from a car fire in 2005 and entered another race a month later.

Since the 1980s, Newman had devoted more time to Newman's Own, a food products company he founded as a lark that grew into one of the nation's largest charitable organizations. The company, which produces all-natural salad dressing, popcorn, sauces and lemonade, has turned over more than $250 million in after-tax profits to hundreds of groups, including his own Hole in the Wall Gang camps (named after the outlaw gang in "Butch Cassidy").

Friends said Newman abhorred what he called "noisy philanthropy." He felt the awards and honors offered him were excessive and once declined a national medal in a letter to President Clinton, calling such recognition "honorrhea."

When people would say, " 'What a mensch you are,' he would always denigrate himself," said friend Alice Trillin. To friends, Newman was open, if vague, about not always having lived an exemplary life. Exceptionally tolerant of others' foibles, he explained, "I used to be a fool myself."

A late bloomer

Friends and neighbors in the Cleveland suburb of Shaker Heights might not have foreseen a future as a sex symbol for Paul Leonard Newman, the late-blooming second son of a sporting goods store owner.

Born Jan. 26, 1925, Newman was too short and scrawny to play football or baseball and once said he regularly had "the bejesus kicked out" of him in school. He was encouraged in the arts by an uncle who wrote poetry and by his mother, who taught him to appreciate music and books and shared details of theater shows she had seen.

Though he acted in elementary and high school plays to the delight of his family, he said his father, a strict, hard-working former journalist, considered him a lightweight and often treated him as if he were disappointed in him.

"I desperately wanted to show him that somehow, somewhere along the line I could cut the mustard," Newman told Time magazine in 1982. One of the great agonies of his life, he said, was that his father died in 1950 without seeing his success.

At 18, he enlisted in the Navy hoping to become a pilot in World War II but was rejected for being color blind. He spent three years as a third-class radio operator aboard bombers in the South Pacific.

Afterward, he enrolled as a 21-year-old freshman at Kenyon College in Gambier, Ohio, where he spent some of his happiest days, playing second-string football, drinking beer and getting in trouble. After a barroom brawl landed him in jail, he was kicked off the team and he turned to acting.

"I was probably one of the worst college actors at the time," Newman said years later. "I learned my lines by rote and simply said them without spontaneity, without knowing what it meant to act and react."

However, novelist E.L. Doctorow, a Kenyon freshman at the time, recalled that "there was no question about his talent." He said Newman was popular for being the leading actor on campus and for the laundry concession he operated.

"He was always entrepreneurial," Doctorow said.

After graduating with a degree in English, Newman acted in summer and winter stock productions in Wisconsin and Illinois, thinking he might eventually teach speech or drama. By then, he had married Jacqueline Witte, a fellow actor, with whom he would have three children: Scott, Susan and Stephanie. Scott died in 1978 of an overdose of drugs and alcohol.

When his father died in 1950, Newman moved home to run the sporting goods store. A year later, the store was sold and he fled to New Haven, Conn., where he briefly studied drama at Yale University, specializing in directing, before trying his luck in New York.

"I was prepared to try it for a year, and, if I got nowhere, to go back to Yale and get my degree," he told Lillian and Helen Ross in the book "The Player: A Profile of an Art." "I had no intention of waiting around till I was old and bruised and bitter."

In New York, then the center of live television and the home of the famed Actors Studio, Newman picked up lessons in Method acting, a technique that stressed naturalism, while he auditioned for parts and sold encyclopedias to support his family. He later attributed everything he knew about acting to the creative community of actors, writers and directors at the studio. At one point, he was president and, though it was never made public, personally financed the institution's operations for seven years when it fell on hard times.

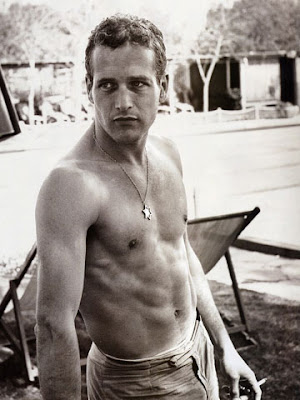

Described as "gorgeous and intense," the young Newman quickly found small parts in television shows such as "You Are There," as well as a role as a rich college graduate in the Broadway production of "Picnic," in which he and Woodward were understudies. When he asked to play the lead, a sexy braggart, director Joshua Logan said the actor was unsuitable because he lacked any "sexual threat" -- a challenge Newman met by embarking on a lifelong routine of vigorous workouts to stay in shape.

His marriage deteriorated as he began to attract work and positive reviews while his wife's priorities shifted to the children, according to friends. Newman then fell into a period of turmoil in which he and Woodward began an affair.

Once he was arrested for running a red light, driving into a bush and leaving the scene of an accident. The breakup of his marriage was long and drawn out, Stern said, because Newman was so concerned about being fair to his wife and children. His first wife obtained a divorce in Mexico in 1957. A year later, Newman and Woodward married, a lasting match that Newman attributed to "correct amounts of lust and respect." The couple had three children.

Despite later rumors that not all was well in their marriage, Stern said the couple were committed and honored each other's choices in life. Although Woodward once quipped that "a mind is a terrible thing to waste on a Trans Am," Stern said, "They had real reverence for each other's talents and pursuits and idiosyncrasies."

Together they appeared in 11 films, including "The Long Hot Summer," "From the Terrace" and "Mr. and Mrs. Bridge." Newman also directed her in four other movies, including the highly respected "Rachel, Rachel," about a schoolteacher whose fears keep her trapped in a small town.

Stern, author of that film's screenplay, said he sometimes observed Newman watching his wife do something that moved him.

"It was the most exposed face of love I've ever looked at," he said. "You couldn't look at it long. It was like opening the wrong door."

Hollywood studios recruited Newman in 1954, at a time when the film industry, threatened by live television, hired many of New York's most creative actors, directors and writers. According to Penn, Newman "was emblematic of what was coming, the demand for independence that the next generation brought."

At first, however, Newman, the serious actor, could not avoid beefcake roles because his looks were so devastating. When people saw him, Penn said, they "just fell away."

Newman was particularly humiliated by his first film, "The Silver Chalice," in which he was cast as a toga-clad Greek sculptor with stilted lines. When the film aired for a week in 1963 on television, he took out a black-bordered ad in the Los Angeles Times that said, "Paul Newman apologizes every night this week."

Determined not to be just a pretty-boy player for the studio, Newman was among the first actors to buy out his contract with Warner Bros. and later formed his own production companies with colleagues. Newman's penchant for playing a variety of roles reflected "his imagination and his willingness to take a flier," filmmaker John Huston wrote in his memoir, "An Open Book."

The price was a career checkered with miscasting and forgettable roles, such as a jazz musician in "Paris Blues," a turn-of-the-century anarchist in "Lady L" and a double agent in "Torn Curtain."

Critics and audiences loved him, however, when he played moody Southerners in films based on Tennessee Williams' plays "Cat On a Hot Tin Roof" and "Sweet Bird of Youth." Newman's scheming pool shark in "The Hustler" began a streak of roles that film historians have hailed as capturing the essence of the postwar American man -- cool, cynical and confident while the known world of traditional values crumbles around him.

Newman became so popular that he complained later that audiences and critics missed the point in "Hud," a film in which he portrayed the amoral, insolent son of an embattled rancher. Instead of seeing Hud as tragically flawed character who cared only for himself, audiences adored him. He became an anti-hero, especially among teenagers. Newman struck another nerve in 1967 with "Cool Hand Luke," in which he played a defiant prisoner on a chain gang harassed by sadistic guards. A memorable scene in which Luke wins a bet by eating 50 hard-boiled eggs triggered egg-eating contests at colleges and among soldiers in Vietnam.

In 1969, when he was Hollywood's most popular leading actor, Newman teamed with Robert Redford in "Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid," a movie about two affable bandits who had outlived their time. The highest-grossing Western in motion picture history, the film highlighted the handsome duo's comic timing. Fans loved the pair's jump off a cliff and still associate the song, "Raindrops Keep Falling On My Head" with Newman's bicycle stunts.

Redford said it was the most fun on a film he had ever had, one that cemented a lifelong friendship between the two actors.

Away from Beverly Hills

If Newman hadn't moved his family away from the glamour and materialism of Beverly Hills to Westport in 1962, he told biographer Eric Lax, he might never have taken up the other things that made his life exciting: politics, car racing and a home-grown business.

"It is only when you're away from California that you cannot take yourself seriously" as a movie star, he said.

Throughout the '60s, Newman took high-profile stands against the war in Vietnam. In 1968, he campaigned for antiwar candidate Sen. Eugene McCarthy and served as a Connecticut delegate to the Democratic National Convention. The following year, he and Woodward joined an antiwar demonstration in front of the American Embassy in London.

Newman knew his actions were not always popular, and told the New York Times Magazine in 1966, "A person without character has no enemies." Friends said he was delighted in 1973 when he was listed as No. 19 on Nixon's enemies list, claiming it elevated him in the eyes of his children. Newman argued politics genially, friends said, and openly admired certain conservatives. In 1994, he helped his brother Arthur, a staunch Republican, wage a successful campaign for a City Council seat in Rancho Mirage.

In the late '70s, bored with acting, Newman fell into a slump that paved the way for what has been called one of the most successful career transitions in movie history.

Intrigued by racing after making the film "Winning" in 1969, Newman began planning film shoots around his racing schedule. His focus, athleticism and knowledge quickly won over skeptics who were used to dilettante actors hanging around the track, said champion driver Mario Andretti.

"If he would have started earlier, he would have been just as successful as his acting, no question," Andretti said. When Newman formed his own team, the Newman-Hass Indy Car, Andretti raced for him for 12 years.

Reinvigorated, Newman returned to acting, exploring character roles with new and unexpected depth. Critic Pauline Kael called Newman's portrayal of a washed-up ice hockey coach in "Slap Shot," a 1977 comedy, "casual American star-acting at its peak." In the 1980s, he became active in the Actors Studio in New York, contributing funds and serving as president of the board.

In 1981, Newman was nominated for an Oscar for his role in "Absence of Malice," as a businessman libeled by Sally Field's gung-ho young reporter, whose story leads to his friend's suicide.

Another nomination followed for his portrayal of an alcoholic lawyer redeemed by his pursuit of justice in 1982's "The Verdict."

When Newman finally won an Oscar in 1986 for "The Color of Money," it was neither his nor director Martin Scorsese's best effort and was seen by some observers as compensation for having been overlooked in "The Hustler."

Wanting to avoid another public defeat, Newman stayed home for the ceremony. Later, he said of the win: "It's like chasing a beautiful woman for 80 years. She finally relents and you say, 'I'm terribly sorry, I'm tired.' "

His real-life role as a model Hollywood philanthropist began just before Christmas 1980 when he and his friend Hotchner made a batch of salad dressing in a bathtub to bottle for friends.

Newman was as much a perfectionist about his cooking as his art, friends said. "He knew the exact amount of fat that goes into the perfect hamburger," Stern said. "In his salads he sliced the celery the exact width."

In restaurants, Newman was known to ask for olive oil, vinegar, chopped celery, salt, pepper and mustard to make his own dressing. On one occasion, when waiters at the legendary Beverly Hills restaurant Chasen's wouldn't comply, he took the salad into the men's room and washed their dressing off. "They brought the stuff he wanted, and he made the dressing," Stern said.

Newman told reporters he never imagined the dressing would be sold nationally, but after the Christmas leftovers were given to gourmet shops, the lark became a challenge.

When it became clear the dressing could make a profitable business, especially with his face on the label, Newman decided to give back some of what luck and the world had given him.

"It was a spur-of-the-moment thing -- 'Let's just do this and give it all away,' " his daughter Nell told the New York Times in 1998.

Newman and Hotchner wrote witty labels to go with the company's motto: "Shameless exploitation in pursuit of the common good," which later became the name of their book that describes their adventures in business.

The company grew to include a range of products including popcorn, salsas, pasta sauces, marinades and Woodward's "Old Fashioned Roadside Virgin Lemonade."

In 2006, he opened "Dressing Room: A Homegrown Restaurant" to benefit the Westport Country Playhouse, one of Newman and Woodward's favorite projects.

As a result of his business success, Newman donated more than $250 million to 1,000 groups -- including the Scott Newman Center devoted to anti-drug education and several Hole in the Wall Gang camps, designed for children with life-threatening diseases, with locations in France, Ireland and Israel as well as the U.S. Every summer, Newman stayed at the original camp in Ashford, Conn., where he told ghost stories and staged shows with other celebrities for children who knew him only as the face on the lemonade carton.

"If I leave a legacy," he said in 2006, "it will be the camps."

This year, he turned up at a meeting of parents and children at the first camp and reportedly said: "I wanted to acknowledge luck. The beneficence of it in many lives and the brutality of it in the lives of others, especially children, who might not have a lifetime to make up for it."

Rather than hiring grant officers, friends say Newman and Hotchner choose the charities themselves in a casual way. Newman once wrote a check on the spot for someone who knocked on his door saying the local fire department needed a new fire engine, said Navasky, the Nation magazine editor.

Despite his fears that actors risk corruption by placing a "premium on appearance," Newman valued keeping himself fit. He did push ups and ran up and down stairs until he was 80. He soaked his face in ice water or would swim in a cold lake when he could.

Newman played "sexy senior" roles into his 70s with films such as "Twilight" and moved on to cantankerous father parts in "Message in a Bottle" and "Empire Falls." He was nominated for a Tony as the stage manager in a Broadway revival of "Our Town," and an Emmy for a taped TV version.

After "Road to Perdition," he did voice work for the animated film "Cars" in 2006 and narrated the 2007 film "Dale" about the late NASCAR driver Dale Earnhardt.

Newman didn't hide his disappointment that filmmaking had abandoned the "theater of the mind" for the "theater of the senses." He lamented that skyrocketing costs had increased the pressure on actors, writers and producers who could no longer afford to make mistakes and be part of a "growing-up process."

In 1997, he hinted he was struggling, explaining to National Public Radio's Daniel Zwerdling that "sometimes you begin to lose your center. . . . You become a collection of the successful mannerisms of the characters you play. . . . What you try to do is get rid of those successful mannerisms, get back to what you are at the core of your own personality."

In 2007, Newman announced his decision to retire, saying he'd lost confidence in his abilities, that acting was "pretty much a closed book for me."

Besides Doc Hudson, the animated Hornet voiced by Newman in the film "Cars," he called the role of Sully in 1994's "Nobody's Fool" the closest he had come to playing himself. Critics called Sully a "classic Newman type" -- an aging version of a witty loner who keeps friends and a family at a distance to protect himself. A bond with his fearful little grandson opens up the possibility of becoming more involved with an estranged son and the rest of the community.

"The most Paul moment," Stern said, "is when he sees the crazy lady down the street and offers his arm and walks her back home as if she were a queen. That's how I'll always remember Paul: dignifying other people."

In addition to his wife, Newman is survived by daughters Susan, Stephanie, Nell, Melissa and Clea; two grandchildren; and his brother Arthur.

His family suggests donations in his name to the Assn. of Hole in the Wall Camps. Information: www.holeinthewallcamps.org.